Antifragile

Again I’d like to lead with the introduction of an important idea and principles from one of my favourite authors Nassim Nicholas Taleb – Antifragile. Here is how he defines Antifragility in his book Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder:

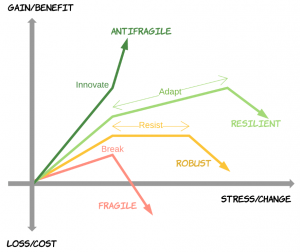

»Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better. This property is behind everything that has changed with time: evolution, culture, ideas, revolutions, political systems, technological innovation, cultural and economic success, corporate survival, good recipes (say, chicken soup or steak tartare with a drop of cognac), the rise of cities, cultures, legal systems, equatorial forests, bacterial resistance … even our own existence as a species on this planet. And antifragility determines the boundary between what is living and organic (or complex), say, the human body, and what is inert, say, a physical object like the stapler on your desk.

The antifragile loves randomness and uncertainty, which also means— crucially—a love of errors, a certain class of errors. Antifragility has a singular property of allowing us to deal with the unknown, to do things without understanding them— and do them well. Let me be more aggressive: we are largely better at doing than we are at thinking, thanks to antifragility. I’d rather be dumb and antifragile than extremely smart and fragile, any time.

It is easy to see things around us that like a measure of stressors and volatility: economic systems, your body, your nutrition (diabetes and many similar modern ailments seem to be associated with a lack of randomness in feeding and the absence of the stressor of occasional starvation), your psyche. There are even financial contracts that are antifragile: they are explicitly designed to benefit from market volatility.

Antifragility makes us understand fragility better. Just as we cannot improve health without reducing disease, or increase wealth without first decreasing losses, antifragility and fragility are degrees on a spectrum.«

So how to implement these ideas in terms of tennis? Let’s go back to the statement I made in the previous chapter: »The matches are decided by moments of brilliance in high pressure and chaotic situations.« The better players should always come on the top in those situations. Volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors help them win, because they are antifragile or because their opponents are fragile, either way, their game in those situations was antifragile because they won in spite of all the chaos on the court.

»In every domain or area of application, we propose rules for moving from the fragile toward the antifragile, through reduction of fragility or harnessing antifragility. And we can almost always detect antifragility (and fragility) using a simple test of asymmetry: anything that has more upside than downside from random events (or certain shocks) is antifragile; the reverse is fragile.«

Let me propose a couple of rules for the application in tennis. Humans and everything in nature is antifragile by default, or it wouldn’t have survived millions of years of evolution. Despite that, fragility still shows when tennis players are put on the court in chaotic scenarios and low probability situations, that can’t be foreseen during practice. The real measure for antifragility are actual matches, so to detect what is fragile and antifragile, in terms of equipment, the test should also be done in match scenarios. I propose that the tests should be done via experimenting with the MGR/I value. From my experiences and observations, the optimized MGR/I value is the closest we can get to being antifragile.